Chels

Happy belated St Patrick’s day!

In celebration, this week I dove into some Irish folk stories.

The versions I read came from Joseph Jacobs and James Stevens’ Celtic Myths: Legendary Tales of Gods and Heroes. Both authors were renowned folklorists, and they did a really great job of capturing the feeling of the oral tradition in their retellings. Most of the stories in this collection come from the Fenian cycle, which Karly talked about this week, but I wanted to start with one that sets the scene for the later stories.

The Story of Tuan mac Cairill

This story tells the tale of Irish history through a centuries-old man, who was not necessarily immortal, but reincarnated into different animals at the end of their lifespan, and as such, saw thousands of years of Ireland. As a young man, he is the only one of the Muintir Partholóin – the second group to settle in Ireland – to survive the plague. Later, the Muintir Nemid arrive in Ireland, and Tuan becomes a stag, then a boar. As a boar, he sees the arrival of the Fir Bolg in Ireland, and as an hawk, the Milesians. He is then reincarnated as a salmon, who is later caught and eaten by the King of Ulster’s wife, finally being rebirthed as her human son.

This all sounds very complex, but Tuan mac Cairill’s tale shows a real appreciation for nature, with some really beautiful passages about nature, especially during the hawk and salmon sections.

There is also a framing story for Tuan’s history, which is his conversion to catholicism by St. Finnan. To me, the story seems to hint at a resistance to catholicism through Tuan’s sublime experience of nature – it seems to me to emphasise the natural beauty of Ireland, and it’s history, prior to the arrival of each group of settlers. However, by the end of the tale, Tuan mac Cairill converts to Catholicism.

I was a little confused by the two seemingly conflicting messages, so I did some research. Early Catholics in Ireland didn’t seek to completely replace the Old Gods, rather, they merged Christianity with Pagan beliefs. I think that is what this story is representing – and Tuan mac Cairill bridges the two belief systems together.

The Fenian Cycle

This cycle begins with The Boyhood of Fionn, which is the longest of all the stories in the collection, and if I’m being honest, my least favourite. But, it gives us important context for the later Fenian tales.

So, the very abridged version of the Boyhood of Fionn is that Fionn’s father is killed by the Goll mac Morna before Fionn is born, and when he’s born, his mother fears for his safety and sends him to live with her sister Bodhmall, and Liath Luachra.

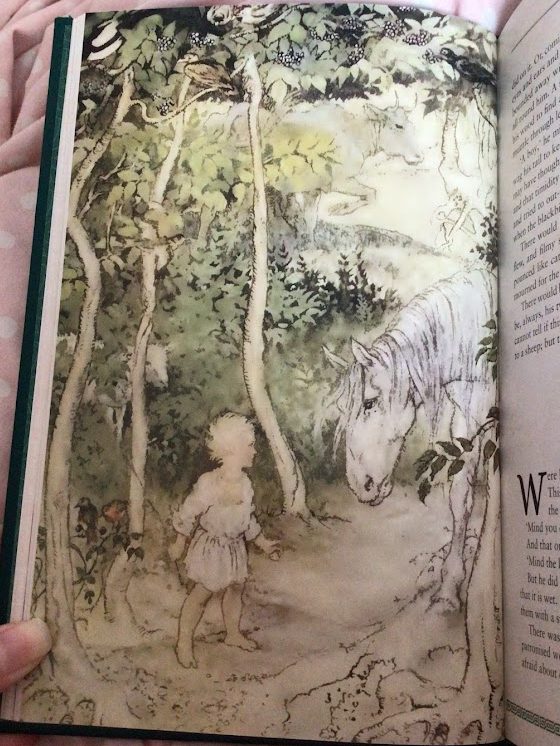

From The Boyhood of Fionn

He goes on a few adventures, during one of which he eats a salmon of wisdom (which, at first I thought would tie into Tuan Mac Cairill’s story, but it didn’t). The salmon wasn’t intended for him, but for his mentor, Finn, however Fionn burns his thumb on the salmon as it cooks and sucks on his thumb to ease the pain, and as a result, he gains the wisdom (and can eat the rest of the salmon).

The version of the story I read talks about Fionns ‘tooth of knowledge, his wisdom tooth’, which led me to think that perhaps this was the origin of the ‘wisdom tooth’. That’s not the case, though, we call it a wisdom tooth because they emerge later in life, around the same time we become an adult, and we’re older than wiser. This is also the only retelling that uses the tooth of knowledge, rather than the thumb of wisdom, so I presume this was a deliberate choice by the writers to link the story to the origin of the name wisdom tooth (which doesn’t really have any folk or mythological meaning).

The Birth of Bran

This tale is about how Fionn’s beloved hounds, Bran and Sceólan, came into his life. I definitely recommend reading this one, but I’m not going to talk about the main story, rather, I want to talk about Fergus Fionnliath. Fergus hated dogs, he would throw stones at them, and reward people who were cruel to them. His role in the story is to care for a dog for Fionn (the dog is actually his aunt, Tuiren, who has been cursed by a sí – don’t worry about it, that’s the main story).

The dog (who is not really a dog), shivers in fear and whines, and Fergus is told that she must be hugged and given affection to stop her shaking. Thinking that his duty is to keep the dog safe, Fergus reluctantly takes the dog in his arms and hugs her, kisses her, and inevitably, falls in love with her.

Fionn later discovers the curse, and rescues his aunt, but not before she bears puppies – Bran and Sceólan. Without his dog – the Queen of Creatures, the Pulse of his Heart, and the Apple of his Eye – Fergus is miserable for a whole year, until Fionn sends him a puppy of his own, who becomes the Star of Fortune and the very Pulse of his Heart.

From The Birth of Bran

I love this tale so much, because it’s essentially the story of every dad who said he didn’t want a dog, got a dog anyway, and it became his favourite child. I really like knowing that it’s the kind of story that’s existed for centuries, it fosters a connection with the past that not all stories can, because it’s something that we can still see happening today.

The Enchanted Cave of Cesh Corran

This is another quite long and complicated story, but it’s the last one from the Fenian cycle in the book, and I think the ending is really important. Fionn and all of the men of the Fianna are captured in a cave by the three daughters of King Conaran of the Sí. They struggle to escape, but eventually, Goll mor mac Morna (possibly the same man who had killed Fionn’s father – it’s a little unclear) kills the three sisters and saves the Fianna. In return, Fionn offers his daughter as a wife.

The final lines of this story are really impactful, at least to me.

‘But that did not prevent Goll from killing Fionn’s brother Cairell later on, nor did it prevent Fionn from killing Goll later on again, and the last did not prevent Goll from rescuing Fionn out of hell … for it is a mutual world we live in, a give-and-take world, and there is no great harm in it.’

This is where the Fenian cycle ended for my reading – with a hint as to how their rivalry and allyship continues. More folk tales exist, but I can’t be sure that all of these stories are told in full. Either way, I really love this ending.

Becuma of the White Skin

Becuma of the White Skin is a retelling of ten Irish folk tales, combined into one overarching story. There’s one in particular that I was really interested in. It poses an ethical dilemma, like an early version of the trolley problem.

A young prince is chosen to be sacrificed to save Ireland from a famine. When the High King travels to claim the young boy, Segda, he tells his parents, the King and Queen that he must bathe in the waters of Ireland to save them, and they agree to this, but cleverly, they place Segda under the protection of all men of Ireland, meaning they cannot harm him. Really, the High King believes that killing Segda and mixing his blood with the soil of Ireland will save them.

This is where the thought experiment is posed. Segda is under the protection of the people of Ireland, so they must not harm him. However, they believe that only his sacrifice will free them from their famine. They must choose the life of the young prince or their own lives.

In the end, his mother rescues him, and explains that Segda’s sacrifice would not save them, rather, they must banish Becuma. So, everyone is saved from making that decision.

I’m really glad I dove into Irish folklore this week. Perhaps we’ll dive into some more folklore later on.

[…] Jacobs and James Stevens’ Celtic Myths: Legendary Tales of Gods and Heroes, and wrote about my favourite folk tales from the […]

LikeLike