Chelsey

It’s a new year, and if you’re anything like me, you’ve spent the last few weeks reflecting on 2024. I didn’t read nearly as much as I wanted to – I found myself prioritising everything but reading for pleasure. This year I’m hoping to get back to it, and to make a dent in my ever growing to-read list.

‘Classics’ can be daunting. Even the name suggests a kind of glorification – what makes them so highly regarded? A lot of the time, they’re compared with modern literature as if they’re a totally different genre (as if ‘classic’ is a genre in itself). It can be off putting, especially when so many of these novels are several hundred pages long, and quite the commitment.

The prestige given to classic novels is a double edged sword – it keeps them in the cultural conversation and on shelves in bookshops, but it can also put a lot of us off from reading them. I’ve compiled a list of ten classic novels that I think are accessible – that is, relatively short books that are pretty easy to digest. Sometimes we tend to think of classics as stuck in the past, but many, including the ones on my list, are still relevant today.

A Room With a View – E.M. Forster

A Room With a View tells the story of Lucy Honeychurch, a precocious Edwardian girl finding her feet. At its core is the blossoming romance between Lucy and George Emerson, and Forster satirises Edwardian English values and the repressed social culture. The story is told in two parts; part one follows Lucy’s holiday to Italy, where she meets George, and part two finds her back in England months later, having been taken home from her holiday early because of her blossoming relationship with George. Of course, the story is a romance, and fate brings the two back into each other’s lives.

In the Cage – Henry James

Another novella which satirises English culture is Henry James’ In the Cage. The unnamed narrator works as a telegraphist and spends much of her working day imagining the lives of her customers based on the telegraphs they send. She becomes involved in the relationship between Captain Everard and Lady Bradeen, seeming to develop feelings for Captain Everard despite her investment in their relationship, and her own engagement. The novella deals heavily with class differences, most overtly through the telgraphist’s friend Mrs Jordan, and more subtly through the girl herself.

The Great Gatsby – F Scott Fitzgerald

The Great Gatsby is probably one of the most well-known stories on this list, and you might have already read it at school. If you didn’t, and you haven’t seen any of the film adaptations, the story is told from narrator Nick’s perspective and follows his interactions with Jay Gatsby. Like the other books I’ve talked about so far, Gatsby is a critique of society – this time, of the New York jazz age. It’s hard to properly talk about Gatsby without spoiling the ending, but I think it’s worth going into this one knowing less.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – DH Lawrence

Lady Chatterley’s Lover is most famous for being censored in the UK (and many other countries) for its obscene content. My copy of the book highlights the ‘previously unpublishable four letter words’ (which I admittedly misunderstood before I read it). The book depicts an extramarital affair between Lady Chatterley and her gameskeeper, Mellors. The book is still controversial – some claim that without the shock value of the obscenity, it wouldn’t still be hailed as a classic, but I disagree. The novel explores notions of emotional and sexual intimacy, and the aftermath of World War one at a domestic level. However, those four letter words are prevalent, so if you’re not a fan, perhaps give this one a miss.

Passing – Nella Larsen

Passing is a short but impactful novella. You can easily get through it in one sitting, which is useful, because it’s also impossible to put down. The story follows three African-American women who can all ‘pass’ for white in 1920s Harlem – and they each make different choices on how they approach their identity. Ultimately, the story ends in tragedy.

Do be warned, though, that the novella depicts the racism the women experience, which may be triggering.

The Wizard of Oz – L Frank Baum

I imagine there aren’t many people who don’t know the story of The Wizard of Oz, but if you don’t, Dorothy Gale is transported to Oz in a tornado and encounters the cowardly lion, the tin man, and the scarecrow without a brain, along with a host of other characters. Originally, it was a children’s book, but I think it holds up for adults too – and the classic illustrations are a beautiful addition to the story.

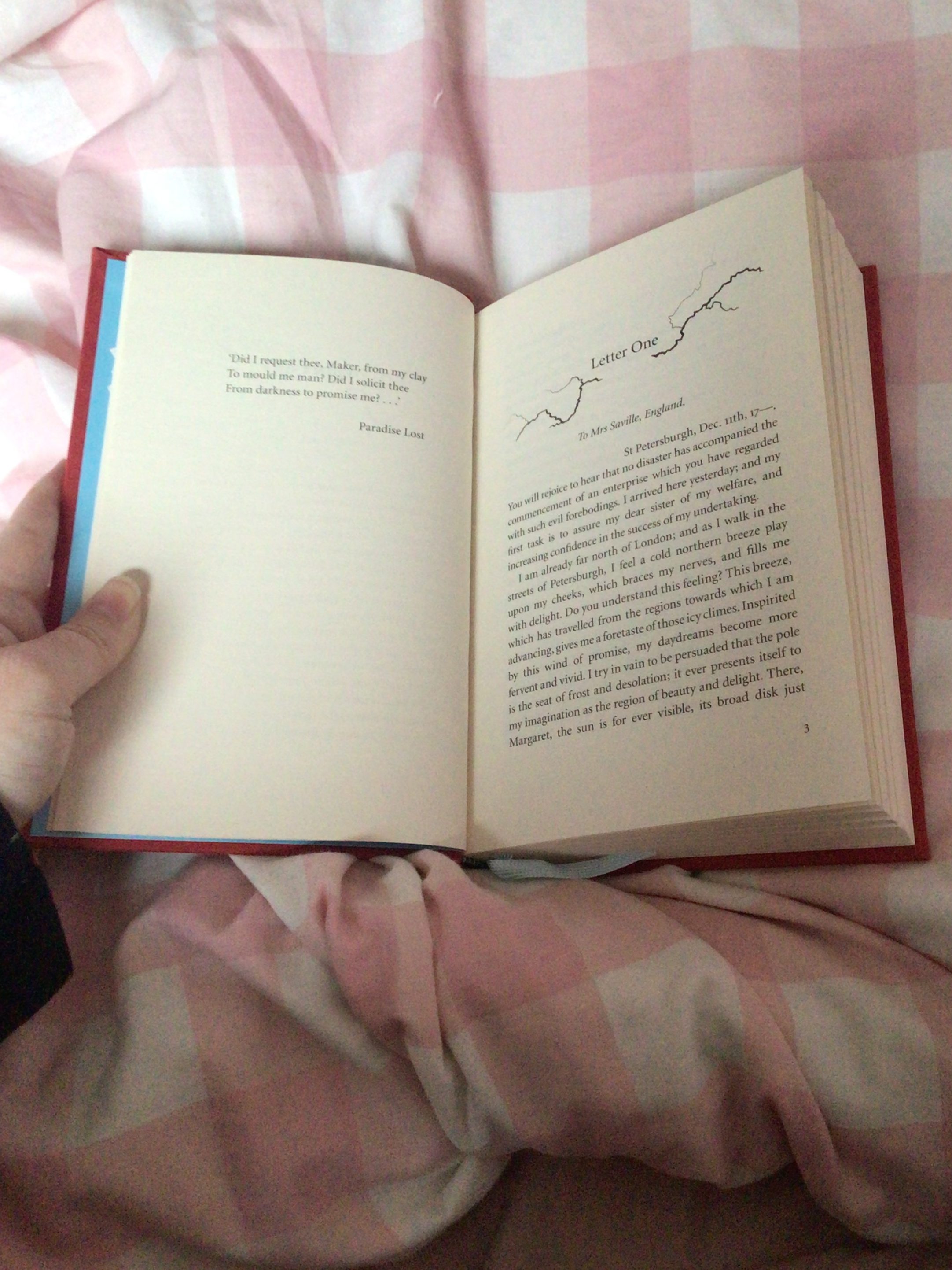

Frankenstein – Mary Shelley

I could spend hours and hours talking about Frankenstein, why it’s my all time favourite book and why everyone should read it. It’s considered the beginning of science fiction as a genre, and it’s had a significant number of adaptations over time, and Mary Shelley was only nineteen when she first published the novel. Frankenstein tackles many themes; class, gender, sexuality, and the family, science and nature, destiny and religion, death and grief, all through the short gothic tale. The eerie horror of the monster’s creation is accompanied by the developments in Victor Frankenstein’s domestic life.

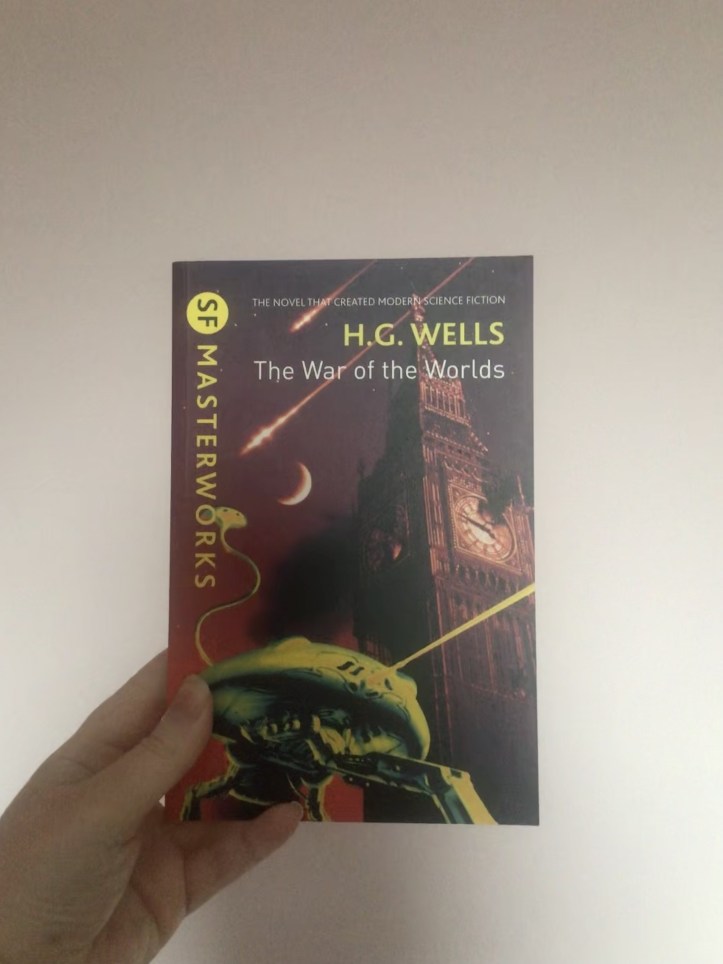

The War of the Worlds – H G Wells

The second science fiction novel on the list is set in Victorian London during an alien invasion. When I read The War of the Worlds, it was May 2020, and the responses to the invasion in the novel were reminiscent of the responses to lockdown, that is, the story felt eerily relevant. Again, it’s hard to talk about the book without spoiling the ending, but I think the resolution of the invasion was unexpected and refreshing – maybe I haven’t read enough sci-fi to properly judge that, but as a novice to the genre, I found it satisfying.

Northanger Abbey – Jane Austen

No list of classics would be complete without Jane Austen. I love Austen’s works, but a lot of them are quite long, and the sheer size of the books can be daunting (I owned my copy of her complete works for years before I actually read it). I chose Northanger Abbey because it’s one of Austen’s shorter novels, so it’s a little bit less intimidating to start. And, selfishly, its my personal favourite of hers. The novel satirises the Gothic novel, but it’s still quintessentially Austen.

Moll Flanders – Daniel Defoe

The last novel on my list is possibly the most controversial choice I’ve made. It’s the oldest (over 200 years old!) and as such, the language leans more towards the archaic side at times. Despite this, I still think it’s overall a fairly accessible read. The story, though long, is easy to follow. Moll Flanders (not her real name) isn’t a faultless protagonist – the story details her many crimes, misdeeds, and questionable decisions, but it’s these faults that made me fall in love with her (and with the novel).