So, by the time this post goes up, it’ll probably already be common knowledge that I studied modern languages and linguistics at uni for my undergrad. However, in case we have not yet got to that point, or you just haven’t read the little bio that I struggled to put together, that’s what I did. To give you a bit of a background, the university I went to has a very Americanised system, full of electives and seemingly useless modules, so no matter what degree you chose, you were stuck with learning a foreign language or furthering your knowledge of English (oh, yes, another piece of Karly lore: I’m not a native English speaker). I’m sure you can imagine little old me’s shock when, as a first-year Psychology student (a story for a different day if you are interested) I find out I’d been placed in German for beginners.

Of course, all’s well that ends well, I was fascinated by German, and let’s say that one module inspired my change over to MLL, but we are not here to talk about how I breezed through a bunch of levels of German and got to upper intermediate in less than a year and then went on to learn Italian during my final year of the degree. Only part of that is true, but anyway, I’m going to talk to you about the myths behind learning another language as an adult, debunking those myths and sharing some of my very own tips and tricks, in case one of your new year’s resolutions was learning a new language. I should also point out that, if any of my friends from undergrad is reading this post, I’m sorry because I’m about to give you war flashbacks to our Second Language Acquisition module.

First, we have to get a bit sciencey for all this to have a substantial background, although if you’re not interested, or if you are a linguist yourself, you can skip this bit. The branch of linguistics that concerns itself with learning new languages is called Second Language Acquisition, SLA for short. I, and a lot of other linguists will tell you that the name is a tad problematic because when one is learning a second language, in most instances it will not be acquired in the same way as one’s first language, it’ll rather be picked up either from the environment or from formal instruction. The other issue with the name of this branch is that it doesn’t only deal with our second languages, it deals with every single language we learn besides our mother tongue, which could be anywhere from L2 to L infinite.

As adults, SLA is often presented as a tricky process when it’s happening in a formal instruction context, and even when done as part of an acculturation process, i.e. moving abroad. This is because of a little thing in First Language Acquisition called the Critical Period Hypothesis, which goes from roughly 18 months old to puberty, where a person is most likely to acquire a new language with ease because of neuroplasticity. Once puberty is reached, your neuroplasticity is obviously not the same, which leads to foreign language learning becoming more challenging.

Now, can this hypothesis be defied? Of course! Otherwise writing this article would be extremely pointless. While I can’t promise you that your neuroplasticity is going to go back to being like a baby’s or that you’ll learn how to speak a language in a week, I can break down some of the factors that influence language learning and what you can do about them.

Motivation

Starting with a big one here. If you want to learn a second language as an adult, motivation is EVERYTHING. In SLA two types of motivation often come up: intrinsic motivation, so something that is personally rewarding, that you’re doing for yourself, like learning French to be able to read Victor Hugo in his native language; and extrinsic motivation, which could be learning German to get a job or pursue a postgraduate degree, something that leads to a reward (or to avoid punishment, but I hope no adult is learning a language to avoid punishment).

There will be moments where you will feel like the learning has plateaued, so to say, but this doesn’t have to discourage you, as it’s natural to make quick progress at the beginning and then have it slow down once you reach roughly an intermediate level. Fear not though, as this doesn’t last forever. My experience with it was different in German because I was doing more formal learning and just the mere level change was enough to convince me that I was actually learning more and not staying in one place. However, in Italian, it has been harder, I know I can perfectly hold a conversation with locals and I can survive on my own in Italy, but I’m still stuck in that awkward spot where I would definitely not feel at ease reading academic texts in Italian, but can understand whatever is going on with Chiara Ferragni and her now ex, and occasionally eavesdrop, and ultimately for me that’s motivational enough. So, I guess what I’m trying to say is, find something that excites you about learning the new language and you’re set. Also, remember learning a language will not happen overnight, it takes anywhere from 6-12 months to become conversational on average, but if you feel more motivated and can devote more hours to its study and have friends who are native speakers available for you to practice with, you may very well reach a high level of fluency far quicker than the average.

Your Native Language

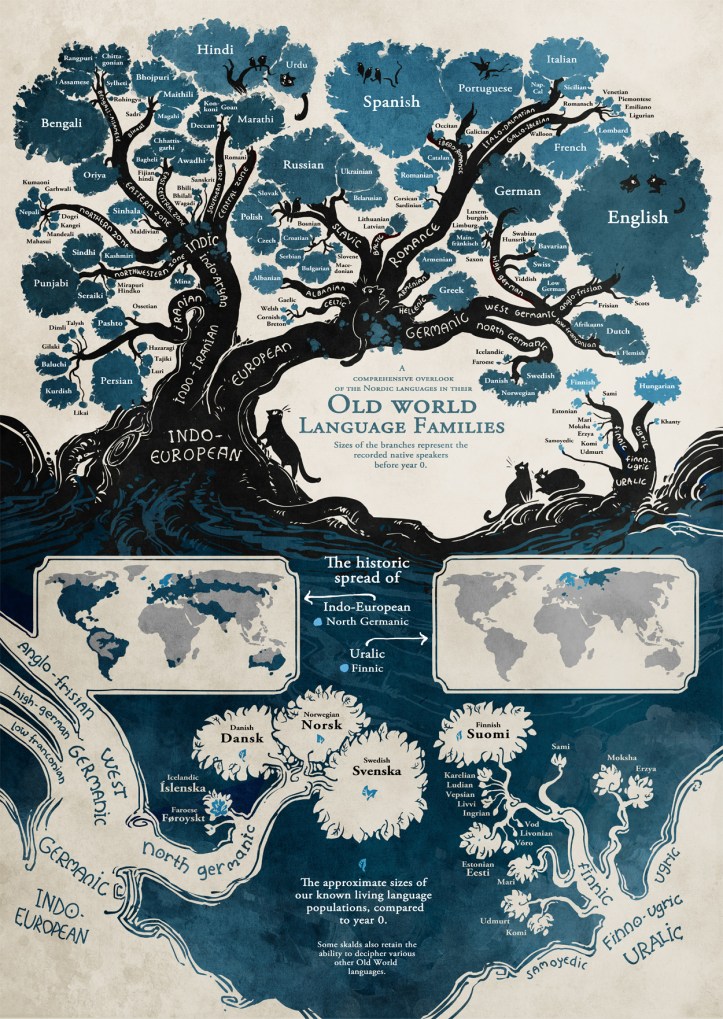

This one often surprises people, but it has a huge impact on how hard or easy it will be for us to learn a new language as adults. There’s this thing called language families, and boy, are there MANY. SLA and linguistics are unfortunately rather Eurocentric so some of the most beautifully detailed family trees like the one below (read more about that tree in particular here) only cover the Indo-European language family in really broad terms. That is not to say it is not useful to illustrate how close or how far we are from our target language. For instance, I, as a native Spanish speaker, am not very far from Italian, which I’m sure contributed to it being a piece of cake to learn even as an adult. On the other hand, in theory, I’m a bit further away from German, but as I grew up bilingual Spanish-English, I was able to learn German through English rather than Spanish. Also, do not take whatever you learned for a foreign language at school for granted if you’re embarking on another language learning journey, chances are if you did French at school and suddenly find yourself interested in Spanish or Italian, however much or little French you can remember can act as a bridge between your native language and your target language.

Your Affective Filter

Ah, never did I think I would be talking about Stephen Krashen for fun, but here we are. Stephen Krashen developed the affective filter hypothesis in SLA, which essentially combines motivation, self-confidence, and anxiety when learning a foreign language. Your affective filter can be high, which means you’re not confident speaking your target language, because maybe you’re very self-aware of possible mistakes, you don’t feel comfortable with your accent, or the instruction environment; all very valid reasons, but they can hinder language learning. If your affective filter is low you feel incredibly at ease with the environment, you realise it’s not high stakes all the time (if ever, unless you’re on a bit of a time crunch to learn), and thus language occurs.

I will say that as someone who has been both self-taught and formally taught, sometimes the dealbreaker can indeed be the teacher, so maybe you’re more at ease learning the basics by yourself and then as you advance onto more advanced levels, find a class that suits your needs, or if you like independence, you can be entirely self-taught. Whichever is best for your affective filter, as that will ultimately help you learn quicker and in a more relaxed way.

Immersion

I have to preface this with a word of advice since I learned this the hard way: immersing yourself in your target language context when you only know the bare minimum is NOT a good idea, especially if you are going to a non-touristy area and are naturally shy and/or anxious.

That being said, immersion, when done right is extremely beneficial, and you don’t have to travel to immerse yourself if you can’t or find that you’re not yet ready to face the challenge of being surrounded by your target language 24/7, you can just consume as much media as you can in the language, and I promise you, you will learn so much, especially conversational styles, slang and more informal things that you would not really learn in a classroom.

If you do decide to take your new language out on holiday or a proper language course in the country where they speak it, my suggestion is, to choose a destination based on how much you want to practise it. When I went to Germany in 2019, I was determined to speak as much German as I could, and that I did, but because sometimes my affective filter was high and I was worried locals wouldn’t understand me, I’d end up sitting on a bench just hyping myself up to go get an ice cream or ask for directions. In the end though, it’s not that serious, locals appreciate you trying to speak their language and will more often than not be friendly and help you, even if you don’t think your language skills are great.

In summation…

- Learning a language as an adult IS doable.

- Find your motivation.

- Consume media in your target language! Magazines are great if you want to start reading before moving on to newspapers and books later on. News shows and your favourite TV shows in their dubbed versions are also great and closed captions are your new besties.

- It might sound nerdy, but flashcards with drawings are great for learning new vocabulary.

- Flashcards in general have been a lifesaver for me when I’ve had to learn verb conjugations. You can make physical ones or digital ones, personally, I prefer physical ones, as you have to write everything down and that’ll activate the learning in your brain.

- Find what works for you: learning by yourself, with Duolingo (can I mention the green owl or does it give too many war flashbacks to a lot of people?) or going to classes.

- Try to find native speakers to practise with if you have the opportunity.

- Embrace making mistakes, you learn from them and genuinely nobody is perfect.

- Have fun! It sounds cheesy and cliché, but learning a new language opens up so many opportunities and gives you new perspectives to see the world in. That’s actually another theory in linguistics which we can talk about another day.

If you have any questions you can comment them here, or go on Instagram to ask them and an expert (me, I’m the expert) will answer them.